In the past, there were only four letters used to describe the queer community as a whole: L for lesbian, G for gay, B for bisexual, and T for trans.

But as the years progressed, more sexual identities and gender expressions have emerged and are slowly being recognized and understood by society. What started as LGBT became LGBTQ and, later on, LGBTQIA+, an acronym that represents the identities of the community.

However, there is one letter in this alphabet soup that became controversial: what does the letter A stand for in the LGBTQIA+?

For some people, they argue that the letter A stands for “ally”, a term that refers to cisgender and heterosexual (a.k.a. straight) people who support the queer community. Other people also say that it stands for both “asexual” and “ally.”

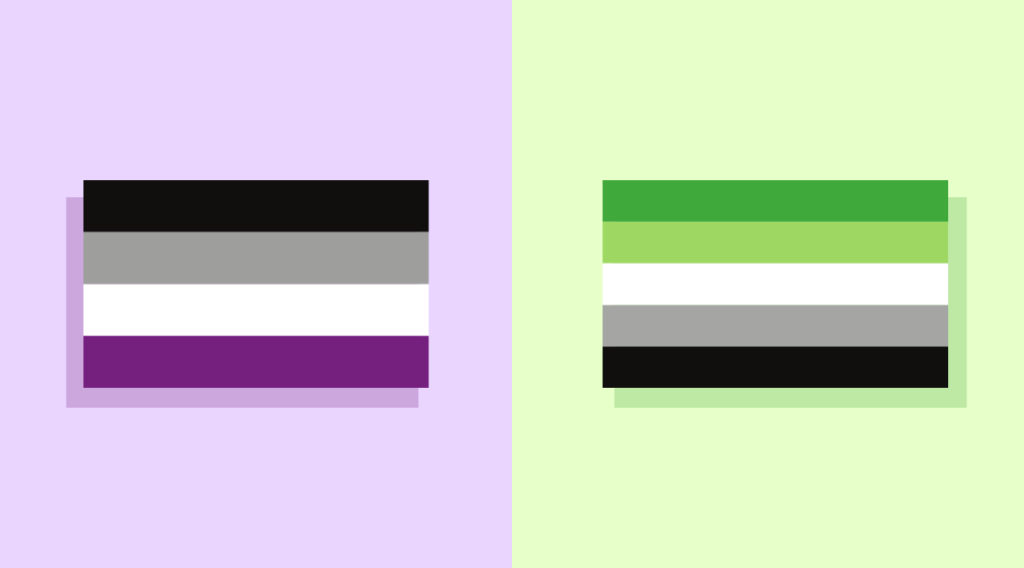

But the letter A actually stands for the asexual, aromantic, and agender identities.

In case you didn’t know yet: asexual refers to people who experience little to no sexual attraction, while aromantic is someone who experiences little to no romantic attraction. Agender, on the other hand, is a person who sees themselves as neither a man nor a woman. But for this article, we’ll be talking more about asexuality and aromanticism.

“The A in LGBTQIA+ has always been for the a-spec,” Angela* (she/her), who identifies as both asexual and aromantic (also called as aroace), says to POP! when asked about her thoughts on the term “ally” being included in the acronym. “Allies are supportive of the community, but they are not LGBTQIA+ themselves, which, I believe, is an important distinction to make.”

Gab* (they/them), who is also an aroace, recalls that she once read that the reason behind the idea of A stands for “ally” is that it was meant for people who are not out yet, “but would like to take part in queer communities.”

“I have no qualms about such individuals using the “A” in that way, knowing that queerness is illegal in many places or against many religious laws,” explains Gab. “But if done to erase and replace A-spec identities, I’m against it.”

Similarly, Asexual Support Philippines representative Ally Ravago (she/her), who also identifies as aroace, expresses her irritation for those people insisting the letter A stands for “ally”, explaining that by assuming this notion, it erases the identities of asexuals, aromantics, and agenders.

“If an individual is truly an ally, they wouldn’t be so offended about not being included in the acronym. True allyship doesn’t need a spotlight,” Ally says.

Much like Ally, Eunice* (they/them) reveal that they are also “disappointed but not surprised” with this argument because even in most LGBTQIA+ spaces, people who identify as aromantic, asexual, and/or both are also excluded since some people in the community think that they are just “straight” and “basically allies.”

“I wish more people knew how harmful it is to steal the space of an already excluded and heavily discriminated group who have always been there fighting for LGBTQIA+ rights right from the beginning,” Eunice states. “This isn’t just for aros and aces, too, this is also for the agenders who have faced the same othering that we [did from] cishets and even the community itself.”

Asexuality and aromanticism as “the invisible orientations”

Both asexuality and aromanticism are two separate spectrums, which means they are umbrella terms with various sub-identities. Therefore, the experience of asexual and aromantic people varies from one person to another.

Some asexual people may also identify as aromantic, while some may don’t. The same goes with aromantics: some may also be asexual, while others may experience sexual attractions.

Both of these orientations are dubbed “the invisible orientations” as they are often overlooked and not discussed by many. As there is only limited awareness of asexuality and aromanticism, some people even struggle to come to terms with their identities.

A case in point, Ally shares that she was only 10 years old when she learned there was something different about her. Unlike her female classmates, Ally didn’t have a crush and because of this, she was teased by her peers and called “abnormal” for not having someone to fawn over.

Two years later, when Ally was being paired with one of her male classmates who happened to have a crush on her, she felt uncomfortable and uneasy. She even recounts that she struggled to name her orientation at the time.

And when she reached the age of 15, Ally encountered the term asexual on Tumblr. She then became curious and learned more about it through the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN). From there, Ally felt relieved and liberated as she could finally put a name to who she was.

Days later, she also read the term aromantic where she went through the process of questioning herself again. But according to her, the process was much “quicker and easier.”

Similarly, Eunice (they/them) shares that they also stumbled upon the term asexual on Tumblr. They recall that growing up, they thought they were pansexual because they had boy and girl crushes as a kid. In fact, their crushes consisted of cartoon and/or anime characters.

Before entering high school, Eunice had heard the saying “mga abnormal lang walang crush” (those who don’t have a crush are abnormal). Because of this, Eunice thought to “‘choose a crush’ from the people, especially boys that I know of.” They admit that the reason why they did it was for people to think of them as a normal person.

This went on for more years until they discovered the term asexual in 2017. Eunice recalls having a sense of pride when they found out about their identity. They also share that while they were sure of their asexuality and gender (Eunice also identifies as a gender non-conforming individual), their romantic orientation was a different subject. It was only this 2022 that they found out that they are aromantic as it took time to find their place on the aromantic spectrum.

“Romantic attraction really is a confusing thing to think about,” Eunice says, looking back on their journey of exploring their romantic orientation. “But I’m proud to say I’m aroace right now.”

Much like Eunice, Gab has also first identified themselves as pansexual. They share that they only stumbled upon the term asexual accidentally when they were 24 years old. As they encountered the term asexual, they felt it perfectly described who they were.

It was only this year, as well, that they also identify as aromantic. They describe being aroace as “loving everyone in a way that’s often nurturing.”

For Angela, she knew ever since she was young that she wasn’t attracted to boys and people around her knew about this, making her feel bad and that there was something wrong with her. There was one point when they even labeled her as a tomboy.

Years later, Angela started to identify as a lesbian, but “lesbian” wasn’t the right term to describe herself as she wasn’t also attracted to girls. At that time, Angela also realized that she had no interest in romance and sex, unlike her peers. Whenever people make fun of her for liking women, she’d told them that she was attracted to both boys and girls, which made her immediate community call her a “weirdo.”

Because of the teasing she received, Angela tried to avoid discussions about romance when she entered university. But one time, she accidentally told her friend that she wasn’t straight and that she can’t love anyone. Her friend didn’t tease her or call her names, but rather she introduced the terms aromantic and asexual.

From there, Angela learned more about asexuality and aromanticism, which eventually led her to put a name on who she was—aroace, making “everything feels so wonderfully and perfectly clear.”

She also says that for her, the idea of being attracted to someone is something that she couldn’t grasp. “[It’s like] listening to a long-winded explanation of a complex mathematical formula when you’re terribly bad at math,” she quips.

Ally, Eunice, Gab, and Angela’s journeys prove that it is important to put a spotlight on and raise awareness about asexuality and aromanticism because this can inspire and empower people to speak up about their experiences in exploring their identities and know that they’re not alone in their struggles. Fortunately, the amount of information about aroaces has increased, and more people are now sharing their stories.

The lack of awareness leads to false beliefs and discrimination

Even though some people now know what asexuality and aromanticism are, we still can’t deny the fact that there’s still a huge knowledge gap between these two orientations.

Speaking with POP!, Gab shares that the main factor that contributes to people not being unaware of asexuality and aromanticism is the erasure of these two orientations.

“Asexual and aromantic people who are not aware of the labels yet are made to feel broken and that our identities are a phase that one may either age out of or abandon once we experience ‘real relationships,’ meaning relationships of a sexual or romantic nature,” Gab says. “And this [also] happens even within queer communities.”

Angela also thinks pop culture plays a part in why people lack awareness of asexuality and aromanticism as most themes being shown center on romance and sexuality.

She notes: “I believe the role of pop culture plays a huge part in awareness since we’re categorically surrounded by it, so if our pop culture only shows those themes, then romance and sex gets further reinforced while the idea of the lack of interest gets further minimized.”

Ally and Eunice also share the same sentiment, pointing out that because this culture emphasizes romance and sex and the practice of amatonormativity (a belief that assumes people prosper with a romantic relationship) and allonormativity (an assumption that people experience sexual attraction), there is not enough representation of asexuality and aromanticism that is being shown or portrayed in the media, which leads to many false beliefs about these orientations as well as discrimination.

“Being aroace is an experience with more indirect bigotry than direct ones with underlying attacks and/or harassments also directed towards other minorities,” says Eunice.

Among the misconceptions aroaces like Ally, Eunice, Gab, and Angela, have also heard and encountered are that:

- Being part of the a-spec is just a “phase”

- Asexuality is a product of sexual assault, while aromanticism is because of domestic abuse;

- Being compared to a plant (and even an alien) for not wanting sexual and/or romantic relationships;

- Aroaces are lonely and unhappy because they don’t have a partner or a relationship;

- Aroaces do not engage in sexual and/or romantic relationships;

- Being asexual means you’re sex-repulsed, while being aromantic means you’re romantic-repulsed;

- Some people think an aromantic person is just emotionally unavailable, while others confuse asexuality with celibacy.

Angela also adds that another misconception about the a-spec is that these identities are something that should be corrected. This notion can lead to discrimination against the people who are part of the a-spec.

“Aces and aros simply do not conform to cisheteronormativity and societal pressures, and others easily invalidate my identity and claim that I’m aroace because I’m ‘just a late bloomer,’ that I ‘haven’t found the right person yet,’ or that it’s just an excuse for me because I’m not in a relationship,” says Angela. “I find the fixation with romance and sex of others so confusing. They always assume everyone wants the same things as them, but I don’t.”

Ways to help spread awareness and be better allies of the aroace community

With these issues raised by aroace folks, it only proves that there’s still so much work that has to be done for the development and increase recognition of asexuality and aromanticism.

So, what can we do to help awareness and be better allies to the aroace community?

“Supporting the platform of asexual and aromantic activists is, in my view, a very effective way to introduce these identities to more people,” Gab says. They then continue to explain that these people are always prepared to educate everyone about asexuality and aromanticism.

They add: “It would [also] be a great path to amplifying our voices through them. There’s so much work to take up, but this is something most of us can do—a step we can all take.”

Gab also shares that people must keep an open mind and listen to the lived experiences of asexuals and aromantics.

For Angela, she suggests that discussions about asexuality, aromanticism, and agender should be included in sex education classes, bring more recognition to awareness events related to the a-spec, and acknowledge and accept the fact that a-spec exists.

“Help us challenge misconceptions and help us tell our stories. But in the end, please remember a-spec exists. We’re true, we’re here, we’re real,” says Angela.

Eunice also shares the tips they read from Smith College’s Asexual and Aromantic Community and Education Club, saying: “[People should] acknowledge that not all people experience sexual and/or romantic relationships, challenge structures that give couple benefits over single people or people in polyamorous relationships, promote ace and aro creators, and support ace and aro representation in media.”

Similarly, Ally says people outside the aroace community can educate themselves about asexuality and aromanticism as there are many resources out there that explain these two identities.

They can also partake in the campaigns organized by different organizations across the world, such as AVEN, The Ace and Aro Advocacy Project, and the Aromantic-spectrum Union for Recognition, Education, and Advocacy (AUREA). Here in the Philippines, Asexual Support Philippines (ASP) is a virtual organization that actively spreads awareness of asexuality.

“What we do in the group [ASP] is [that] we share articles, infographics, videos, and whatever else we can to our members and the public at large about asexuality and aromanticism,” Ally shares.

“We also try to participate in outside opportunities such as interviews and panel discussions to raise awareness. We’ve also had a few members who have done research work on asexuality for their university studies, and we have expressed our support because we think it could be a big help, especially to the academic community here in the Philippines, that could lead to further research and study,” she adds.

If you wish to learn more about Asexual Support Philippines and the a-spec in general, go check them out here.

A message from one folk to another

Angela, Gab, Eunice, and Ally also share some words of wisdom and bits of advice to the aromantic, asexual, and aroace folks, and to those who are still exploring what part of the spectrum are they.

“Take up space, it belongs to you. You’re not broken, you’re real, and you’re here. Love you (platonically),” says Angela.

Gab also encourages the community to “hold on and listen to our inner voice.”

“We are queer, and we have a seat at the table. We must also keep our hearts open, to not automatically react defensively to questions and general confusion,” adds Gab. “Keep calm, love dragons and eat cake—there is no one-size-fits-all in the umbrella of identities that belong to asexuality and aromanticism.”

Likewise, Eunice also stresses that “there’s no wrong way to be ace, aro, or to be aroace.”

“Like what I’ve told my friend before: whatever you may call yourself right now MAY or MAY NOT stay as the label you use, because the aro/ace/aroace experience overlaps with one another and have so many confusing terminologies under them, says Eunice. “But remember that that still doesn’t erase who you identify as of right now. Who you are right now is not a lie, you are who you say you are at this moment even if it ends up changing.”

They continue: “Live your truth because people will always obsess over you regardless if you’re enjoying yourself or not!”

Eunice also recommends watching a video by Jaiden Animations that can help the questioning aroaces to know about themselves.

Ally also reminds their fellow aromantics and asexuals that they’re not alone, broken, or abnormal for embracing who they are.

“There is no such thing as ‘not asexual/aromantic enough.’ Asexuality and aromanticism are both spectrums—we all have our unique perspectives and experiences, and we definitely belong at Pride,” says Ally.

“I [also] want my fellow aromantics and asexuals to take their time to come out. It is not something you do for others, especially if you feel like you owe them. Coming out is meant for you and it is meant to be freeing. If you feel like you’re not in a safe space yet to come out, then don’t,” she adds.

*Three of the interviewees featured in this article used nicknames for anonymity purposes.

Other POP! stories you might like:

10 local organizations that foster safe space for the LGBTQIA+ community

Coming out is something personal, and should never be forced by anyone