For those of us who came of age in the ‘90s, that decade was tremendously influential in the development of our entire generation’s sensibilities and attitudes. The Marcos dictatorial regime had just fallen a few years before, the economy was in shambles, while the lingering euphoria of EDSA revolution voted in power a former rebel soldier. We saw the rise of MTV and Japanese cartoons, the gags of “Tropang Trumpo,” the funny banter of istambays in “Home Along Da Riles.”

The kids were raucous, impulsive, and entertained, unaware of the Asian financial crisis, the warplanes flying over the Gulf, or the evil of Saddam Hussein. We thought rotating brownouts were normal, that standing in line for rations of water and rice was normal, everything seemed normal, so long as we could play outside, away from the adults and their preoccupations. Nothing scared us, we thought life would stretch to our desires. We had dreams, we were young and unscarred, hopeful and headstrong. We were oblivious. We watch the stars at night. The world was at peace, rushing forward into the future.

Everyone has a hobby, and nothing was frowned upon. You could learn an instrument, collect cassette tapes, draw pictures, study martial arts, admire Bruce Lee. But somewhere down the line, something comes up and everyone takes notice. At a certain distance, we take a step back and observe. Our friends were moving on from one hobby to the next, but this next one was something we didn’t expect: Cross-stitching.

Origins of cross-stitch

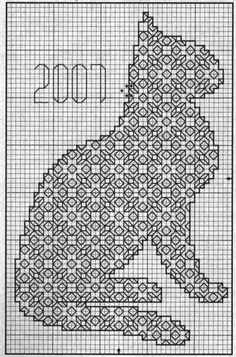

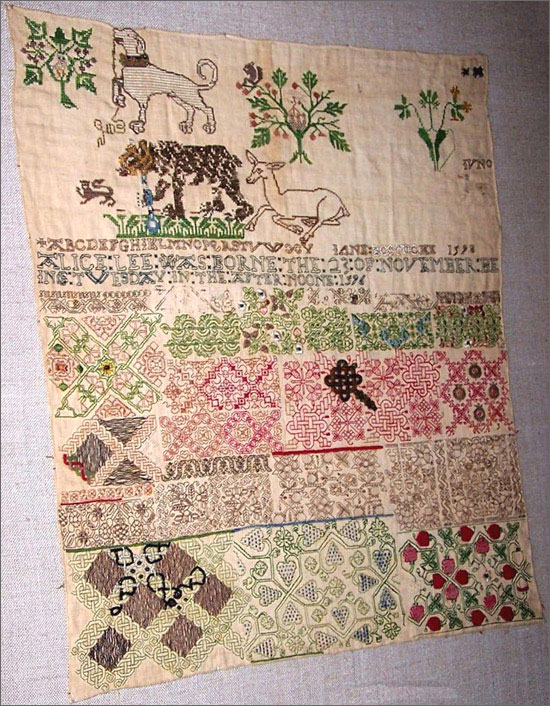

Cross-stitch is a traditional form of criss-cross embroidery that originated from Asia, Egypt, and other parts of Europe. Some of the oldest works can be traced back to 200-500 A.D. Geometric and floral patterns were usually embroidered on a white linen using evenly-numbered threads. One certain type is called “blackwork,” where wools from black sheep were used to depict rural and pastoral scenes. It was a popular pastime in Europe, where children used to embroider religious verses on pieces of cloth. Others, however, create “samplers”, which are “commemorative” pieces consist of messages about life, death, birth of a baby, and remembering departed loved ones.

The modern style we have today is called counted-cross stitch, since you must count the number of stitch to build the figures. It is created this way since the holes in a canvas, the white linen, are evenly numbered from left to right.

The Cross-stitch Craze

I remember the day I first saw it. Inside the classroom, the teacher was instructing our class on a new project. She brought out a white cloth tapered to the rim by a thin, circular wood. Then she took a paper with a printed pattern, guided a thread into the needle-eye. Watch closely, she said.

Count the numbers in your pattern, make a criss-cross from the line, follow the path, then go to the next holes. It’s that simple. And I did the same thing. It was hard work counting, and many of my classmates were very adept at it. I was working at a glacial pace, my threads bunched unevenly on the canvas. But the girls rocked it so hard, though. They were absolutely good.

The next thing you know, everybody is doing it: housewives, adolescent girls, your neighbours and friends, even your mother. Inside homes, or outside, or while riding jeepneys. The media caught up, and we saw celebrities on TV strutting around with their cross-stitch kits. It had turned into a business for some, as well. The lazy students, usually boys in our class, would pay P150 to a known cross-stitch maker to finish their projects, and the orders piled up.

Then, the trend died – suddenly, and without warning. The needles were shelved, the canvas rolled. We passed our projects, the teachers graded them. Everybody moved on.

Death and the Aftermath

Why did we start it in the first place? Was it the inspiration to make art? Have we been gripped by the power of thought, I am bringing this object into life? Or was it the appeal of starting something small and admiring at the whole when it’s done, the tenacity to make something beautiful with our own hands? A young girl on a swing, a platter of fruits, a meadow with a lone house in the distance, a magician in brightly-coloured dress standing on the clouds. We were transfixed at these images. For a moment, we thought they existed alongside us.

The quicker the cross-stitch trend arrived, the sooner it faded away. We grew up, we shed our dreaming selves, we found other ways to divide our attention. We kept up with every new trend that came along, measuring our profiles with the lives of celebrities. We looked outwards, rather than inwards, a generation that was taught to know ourselves first, but forgot it in the process. You can’t say people had no time for hobbies. It wasn’t an enough excuse, no one had. It wasn’t time that we lacked, only concentration. The ability to sit still for long periods at work, with intense focus and absolute mindfulness. That’s what we lost, and probably only a few regained it, in later life.

We were on the cusp of the millennium, and we eagerly awaited it. The century was turning, an entire civilization looked ahead, thrilled by the promise of technology: the advent of cellular phones, the rise of the internet, of an interconnected globe.

At this point, someone reading this might say, “You cannot put the blame on our generation. The loss of focus would have happened anyway, with or without cross-stitch! Something equally like it would have replaced the thing.” And perhaps it’s true. Maybe, the phenomenon is more nuanced and complicated than the explanations offered here, and it’s better not to hazard a conclusion. Perhaps, with the passing of time and with a sober hindsight, we’d be able to figure out the reasons, and only time will also tell whether we have been richer – or poorer – for abandoning it.

Will the cross-stitch craze make a comeback soon? We hope yes. Will it survive another generation? Definitely.

/VT

Other POP! stories you might like:

The eternal flame of Philippine motels

Really, we’re curious: Why do ‘apartments for rent’ in the Philippines look like this?

The NPC TikTok trend has now reached the Philippines

Revisiting the music of Vanna Vanna, the Philippines’ R&B girl band of the 90s

‘Kulay’ and the color of their music