In the beginning of June, Twitter user Lily Kay Ross, PhD decided to create a thread unpacking the term “perfect victim” which shows a lot about society’s views on gendered violence and the aftermath of this.

The "perfect victim" keeps cropping up in talking and writing about Amber Heard and the trial. I did my PhD research looking at the construction of the victim and survivor labels in the context of gendered violence. We can learn a lot by unpacking the "perfect victim." A 🧵

— Lily Kay Ross, PhD (@LilyKayRoss) June 5, 2022

According to Lily Kay Ross, PhD’s Twitter bio, she is a “sexual violence researcher”, feminism and ethics research fellow, as well as a content creator. Ross mentioned that she did her PhD research on “the construction of the victim and survivor labels in the context of gendered violence.” She also included supplementary reading links and even the link to her entire PhD thesis entitled The Survivor Imperative.

And any nerds interested in my PhD thesis can access "The Survivor Imperative" at this link, and there's more coming this fall in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society."https://t.co/7i9QowvluP

— Lily Kay Ross, PhD (@LilyKayRoss) June 5, 2022

Her thread was just a brief portion of her thesis, providing a type of TL; DR (too long; didn’t read) for inquisitive scrollers.

According to the thread, the originator of this concept was Norwegian criminologist and sociologist Nils Christie in 1986. The “ideal” or “perfect victim” is “a person or a category of individuals who—when hit by crime – most readily are given the complete and legitimate status of being a victim.” These are the people that would “most deserve” the title of “victim” after being attacked.

There are 5 attributes that someone must fit into in order to be labelled as a “perfect victim” thus “worthy” of complete sympathy. The person must be weak. At the time of their attack, they must have been doing something respectable, and in a place that they could not have been blamed for being in. In terms of the assailant, the victim must have been attacked by someone who was “big and bad”. Additionally, they would have to be attacked by someone who is a stranger to them.

These 5 attributes alone already make it impossible for people who were attacked by their spouses/partners, or anyone that they know, to come forward about being attacked and hope for sympathy. But wait, there’s more.

Ross also mentioned Christie’s listing of two contradicting yet essential ways “for how victims ought to behave in order to be treated sympathetically”

First is to “take responsibility for themselves and the harm that befalls them,” and to use their trauma to grow and become better/stronger people. While discussing this, Ross mentions a piece that speaks about resilience and the harm that rigid enforcement of this may result in.

better/stronger/more enterprising through trauma. This is the danger of "resilience," and highlights the cruelty of enforcing resilience. @SaraNAhmed writes about this insightfully in Living a Feminist Life. pic.twitter.com/N4A9OMljzO

— Lily Kay Ross, PhD (@LilyKayRoss) June 5, 2022

Failure to act according to this requirement would make the person vulnerable to being accused of having a “victim mentality”, that they believe that being a victim is inherent in who they are as a person rather than a result of real-world events and injustice which they can’t control.

The second behavior is that victims should have a “Christ-like” response. They must be forgiving, “turning the other cheek”, and endure the suffering.

Failure to act according to this may result in “reactive victim scapegoating”, where victims are painted as aggressive villains because of a response that is anything but meek. Ross quotes that these victims are received negatively due to their “resilient coping style. It seems to have been precisely their autonomy and activism that has triggered negative responses.”

Here lies the paradox of these two behavioral requirements that make a perfect victim. Living up to one of these would mean contradicting the other. If you follow behavior #1 and take a proactive response after your attack, you will be seen as callous and aggressive in the context of behavior #2. If you follow behavior #2 then you will be seen as unassertive and passive.

Perfect victim, as a whole, may be viewed as limiting a person’s agency—specifically those who have been most vulnerable to gendered violence, who Ross names as women, trans, and non-binary people. It limits the behavior and reactions that people can have. You deserve less sympathy if you were engaging in “risky behavior” such as walking home late at night, and if you fight back against your assailant then you may be perceived as a cold and rogue person.

Earlier (and even some present) suggestions to counter these may also be seen as policing the victim rather than sentencing the attacker: don’t walk home alone at night, don’t drink excessively, don’t wear clothes that are too revealing… These further control the bodies of women, trans, and non-binary people and may even suggest to victims that they could have avoided what happened to them if only they were “more careful”.

These responses put the burden on the victims, women, trans, and non-binary people to protect themselves and be responsible in predicting violent actions of those around them. It tells them that it was their fault that they put themselves in a certain situation and let down their guard, making themselves vulnerable. But we must remember that people are not only attacked in public in the dead of the night by some shady stranger, numerous cases are also of violence within the privacy of someone’s home with someone who they may have even loved and trusted.

In short, there is no way that you can win. No matter how you decide to tell your story, society would find a way to contradict your response and find something to critique about it. This could result in backlash, hostility, and even victim blaming—following what was already a traumatic physical and/or emotional attack. It makes victims think that staying silent is the only way to avoid the burden of speaking up.

“Speaking up about our lived experiences should not be so hard,” Ross eloquently puts it “the fact that it’s hard creates a barrier to looking at what actually caused victimization in the first place”. Upholding the unrealistic standards of the perfect victim and enforcing them on victims will only continue to keep more of them in the shadows, hesitant to come forward.

With all the talk of perfect victim, Ross breaks this down even more and tackles on the term “victim” itself which has faced some push back. Ross describes herself as “an advocate for embracing the term and the label for political purposes and solidarity,” she believes that the term is more uplifting than derogatory.

Being called a victim lets people know that something harmful actually happened, it was something you did not want, and no one deserves to go through this. It brings legitimacy to claims and places responsibility on those who caused harm.

Ross quoted Carine Mardorossian in saying that in the 1970’s “being a victim did not mean being incapacitated and powerless. It meant being a determined and angry (although not pathologically resentful) agent of change.” Being a victim is not about who you are as a person but rather the effect of someone else’s choice to harm you.

With so much to say in such a concise thread, Lily Kay Ross, PhD’s words were more or less received positively. People were thankful for her sharing the short sneak peek into her research. Most believed it to be a useful and relevant thread.

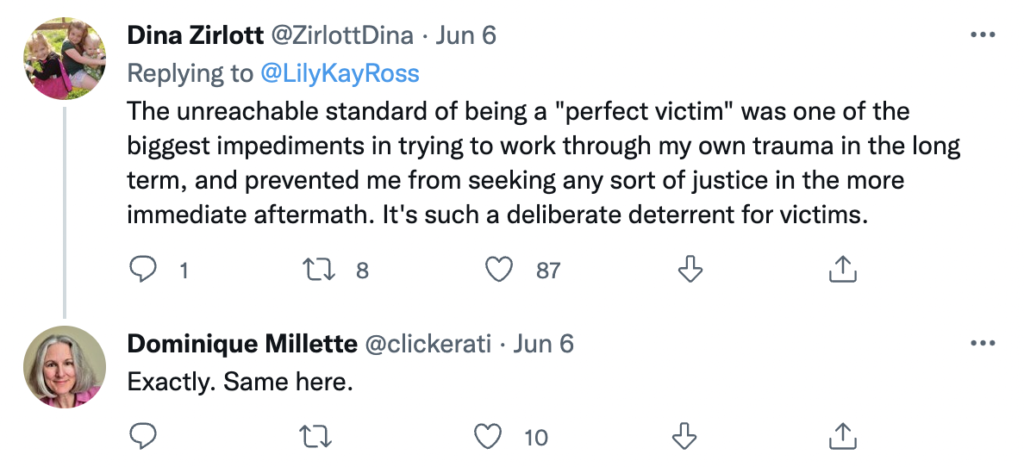

Some users even mentioned that it was the concept of the “perfect victim” that hindered them from fully processing the trauma that their attacks resulted in. The feeling that they might be undermined for not 100% adhering to the standard set of a perfect victim kept them quiet.

Lily Kay Ross, PhD mentioned that one reason why she decided to create her thread was because she saw the idea of the perfect victim creeping around when people discussed the Amber Heard/Johnny Depp trial.

In the second half of a post-verdict interview with Savannah Guthrie from NBC News, Heard herself states that “I’m not a good victim, I get it,” adding that “I’m not a likeable victim, I’m not a perfect victim.”

Amber Heard addressed the public’s perception of her, believing that Johnny Depp was able to keep his promise of having her face “total global humiliation” which he said via text.

The very intimate trial was put on the air for all to see, unfortunately allowing a lot of clips to be taken out of context, remixed, and memed despite the very sensitive issue being discussed. As a Refinery29 article put it: “passing judgement on the intimate details of their relationship became a spectator sport.”

Whether you were religiously following the Heard/Depp trial or not, it was possible that you still saw sprinkles of it scattered over your various timelines. This was especially a critical factor to take note of, considering that the jury was not sequestered. With most of the backlash being directed at Heard, it may have been unavoidable to create a biased opinion before her camp even had the chance to testify.

Every movement of Heard was criticized and she herself, crying while trying to explain a horrible experience, was turned into a laughingstock.

“I’m scared,” Heard declared when asked about Depp possibly suing her again in the future, “that no matter what I do, no matter what I say or how I say it, every step that I take will present another opportunity for silencing”.

While the trial, and the actions of both Depp and Heard leading up to it, were very much a cause of intrigue, it is possible that the treatment of the case online could have added fuel to the fire of the drama.

Both camps had their faults, but in the end, both were rewarded damages. Depp took a considerably larger amount with $15 million while Heard was bestowed $2 million.

Like she said, Heard is definitely far from being a perfect victim, but the villainization of one person does not excuse the other. Just like Heard, Johnny Depp is far from perfect—although, unlike Amber Heard, his mistakes were not put under the social media news feed microscope.

For example, it may have been lost upon some people that Johnny Depp once sent out graphic texts about Heard, saying that he “will fuck her burnt corpse afterwards to make sure she’s dead,” even describing her body in other messages in deeply derogatory ways such as “mushy pointless dangling overused floppy fish market”.

Lucia Osborne-Crowley, a reporter who tackles courtroom proceedings, told Refinery29 that “I’m really concerned by the response I’ve seen to the Depp/Heard trial and not because I am on her ‘side’ or believe that all her allegations are true,” she explains that the “tone and content” of the backlash is alarming. Osborne-Crowley also points out that a big chunk of the criticism against Heard “perpetuates long-debunked myths about domestic and sexual violence” with a lot of them talking about what a “real” victim would or wouldn’t do.

Osborne-Crowley also expressed concern about “the fact that so many social media users are making jokes out of her testimony.” She believes that it doesn’t matter whose “side” you’re on or how much you believe Heard/Depp, but jokes about rape are never okay. “I wish people would critique her evidence and her story without making a mockery of what are very serious allegations of criminal behavior,” she adds.

Osborne-Crowley’s statements were recorded before the verdict came out, but they remain relevant and salient. “Whatever the truth,” she said, “this was clearly a very damaging and traumatic relationship.”

“There is a myth,” she adds, “that a person has to be good or moral in order to have been subjected to domestic abuse.” There is no one way to be a victim of an abusive partner. We all respond to things differently, even more so when something traumatic happens to us, depending on our own past experiences and coping mechanisms. In the case of Amber Heard, she responded with violence. Dismissing her claims because of this reality is similar to implying that victims don’t fight back, but they can, and they do.

At the end of this trial, we may have learned more about our society than the private relationship of Amber Heard and Johnny Depp. In a RollingStone article, sexual assault survivors were interviewed about their thoughts on the trial and its verdict.

“It’s a scary place to be,” someone stated. For most of the survivors it was terrifying to watch, like their worst nightmares being televised on screen. “Survivors watching this will rethink everything they say out loud about what happened to them,” one person mentioned. It wasn’t only that Amber Heard came out with such serious claims, it was also the way these were received, with the clear verdict just adding on more weight on top of that.

“And survivors must deal with the implications attached to the verdict,” EJ Dickson writes in the Rollingstone article, “that women who come forward against powerful men may not only not be believed, but actively punished.”

This is all is not to invalidate the side of Depp either. Lily Kay Ross, PhD said herself, towards the end of her informative thread, that men can (and do) experience victimization as well. She also called for the need for more research to be done regarding this—although underlining that it must be executed in such a way that does not “undermine or discredit men’s victimization of women, trans, and nonbinary folx.”

In the context of the Heard/Depp trial, again, neither of them was “perfect” and they didn’t have to be—no one is, and no one needs to be “perfect”. The topic of gendered violence continues to be a delicate and sensitive matter which needs to be treated accordingly, with earnest compassion and empathy. Holding on to the “perfect victim” will only stop us from lifting up someone who is reaching out and speaking about their pain. We need to be open and willing to understand not only that this violence happened but also why someone would react to it in a certain type of way.

The whole idea of destroying the concept of the perfect victim and the stigma it creates is to understand that there is not just one way to react to gendered violence/ be a victim of it— more than scrutinizing a person’s response, it may be more prudent to analyze why this situation was able to unfold in the first place.

Why did this happen and how can it be prevented from happening again? This isn’t at all to say that we should completely disregard the victim, but it means to listen to their story, wholly acknowledge their response, and embrace them in order to prevent any more people from becoming victims themselves.

Other POP! stories you might like:

Amber Heard’s sister calls MTV ‘desperate’ over Johnny Depp’s cameo at the VMAs

All treats, no tricks this Super Halloween at SM Supermalls

Discipline should not require physical abuse, so stop justifying corporal punishment

Budget friendly ways to spend your ‘Undas’ break