What makes a character well written? Is it their deep and realistic motivations? The way they talk to themselves and those around them? Maybe you’re into those morally gray characters that would lowkey make for some problematic and toxic s/o’s.

With the plethora of characters that exist, there are bound to be some similarities between them. Sometimes authors inject parts of themselves into their stories and into the characters that they write. And, hey we’re all only human so sometimes the similarities between characters make sense. But while authors injecting themselves into their characters can provide a sense of authenticity to the character and their story, it can also sometimes lead to characters becoming flat and less complicated, like the Mary Sues of the literary world.

What is a Mary Sue? Well, it’s one of the many types of characters that exist out there in the creative world. A Mary Sue may be related to The Girl Next Door, or even the distant cousin of a Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

Mary Sue is a term that has been used around the fan fiction realm and all over pop culture, but over the years, its definition has gotten muddled, and it’s even been used as a front to slip in some hidden sexism against strong female characters.

Believe it or not, the term “Mary Sue” was born in the world of Star Trek fan fiction in 1973. When Paula Smith and Sharon Ferraro began the Menagerie, a fanzine dedicated to the Star Trek universe and fan fiction involving it, they noticed a pattern in some of the fan fiction submissions that they were getting. Majority of the stories centered around a certain type of character.

This character, often a young woman, was usually just “so sweet, and good, and beautiful and cute,” Smith recalls, “everybody would just fall all over her.” After almost 4 decades since the Menagerie was discontinued, both Smith and Ferraro can still recall the exact submission that inspired the term “Mary Sue”.

The story followed a young, amazing, and beautiful protagonist whose grace was so limitless that she decided to sacrifice herself for the sake of the crew’s safety. In the 80-page, back-to-back, story, she finds a way to later resurrect herself and put an end to the mourning of her crewmates. “I’d never seen that one anywhere else,” Smith said, “so, I have to give [the writer] kudos for that.”

While the Mary Sue label can be given to any character, no matter their gender, it was common for female characters to be called a Mary Sue. At the time of the Menagerie, Smith and Ferraro attributed it to the large female fanbase that Star Trek garnered. “Science fiction fandom, in general, was like 80 percent men,” Ferraro estimates, “Star Trek’s fandom was the exact opposite; at least 75 percent women.”

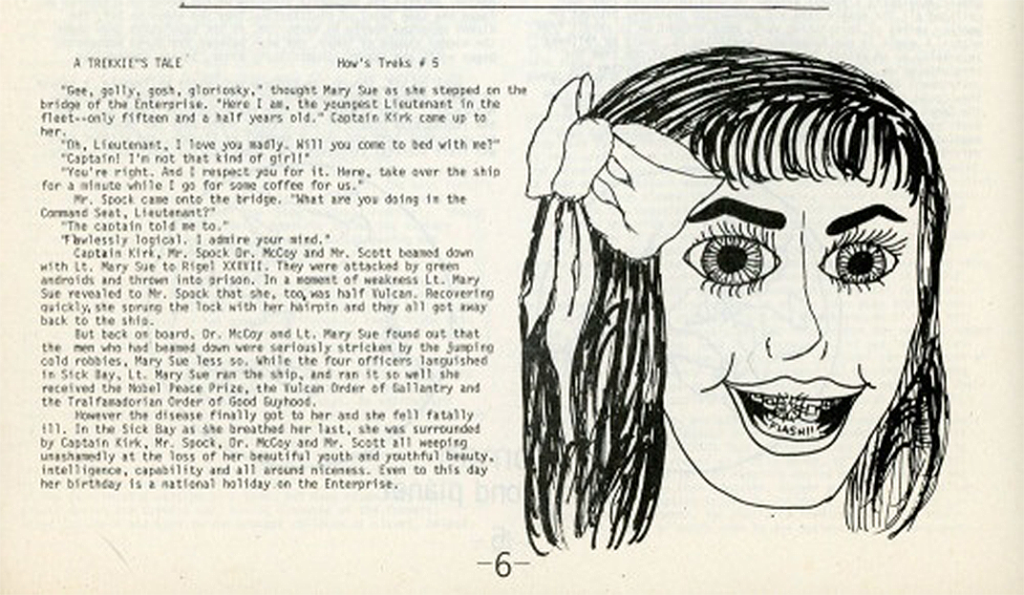

After seeing enough Mary Sues to last a lifetime, Smith decided to create her own take on the character in a parody titled A Trekkie’s Tale. With an opening line of “Gee, golly, gosh, gloriosky” A Trekkie’s Tale starred the one and only Mary Sue. At the tender age of 15 and a half years old, Mary Sue was the youngest lieutenant in Federation history. Along with this prestigious record, she also won the heart of the one and only Captain Kirk who immediately proposed a risqué bedroom date to which Mary Sue replied that “Captain! I am not that kind of girl!” This only makes him respect her more, so much so that he lets her man the ship while he goes for a coffee run for the two of them.

Of course, everyone’s favorite Vulcan, Mr. Spock comes over questioning what she’s doing in the captain’s chair. After she explains the situation, he responds that it was a “flawlessly logical” choice. The short but concise story ends with Mary Sue’s heroic demise, after being given a handful of awards, with the crew weeping “unashamedly at the loss of her beautiful youth and youthful beauty, intelligence, capability, and all-around niceness.” The Enterprise also makes sure to turn her birthday into a national holiday out of love for Mary Sue.

Suffice it to say that the term “Mary Sue” was used much more commonly after the release of A Trekkie’s Tale. The definition of a Mary Sue was later determined as a writer’s self-insertion of themselves into a character. Mary Sues were characters that were author’s idealized versions of themselves put into their world of choice. They were perfect in every way, and if they were flawed, it only added to their overall endearing effect. The term Mary Sue is applicable to any character regardless of their gender. Smith and Ferraro tried experimenting with gender bends of the term like Murray/ Marty Sue but felt that Mary Sue was the best fit. Despite its origins in the Star Trek universe, the term has been used across many different fandoms since then.

Smith explained that the fan fiction containing Mary Sues were “placeholder fantasies”, not to say that she doesn’t have these as well. Mary Sues were then viewed as almost a rookie mistake in writing. Not dissing or disregarding self-insert characters completely but suggesting that their Mary Sue characters have some room for improvement.

Self-insert characters allow women and underrepresented communities to place themselves into universes they love and dream of, which is a great thing. While Mary Sues may be seen as a flat character, Elizabeth Minkel believes their existence to be more meaningful. She explains that Mary Sues are about “young girls finding their power and agency in a world of fictional landscapes that rarely afford such journeys to women.” It allows writers to view themselves and their potential in distant and magical worlds which is a whole power in and of itself. For most, Mary Sue characters may be a phase of writing that is hard to avoid but is nevertheless a (sometimes natural) step on the journey into improving one’s writing skill.

So, Mary Sue is just a term to describe a character type who is a less complex, over idealized self-insert of an author with character development that can be further improved, right? So, where did things get out of hand?

While the growth of the term’s use widened, its definition started to get lost in the sauce over time. As it expanded outside the realm of fan fiction, Mary Sue was now being used as a derogatory term targeted at protagonists, usually female, who were generally disliked because of their power and/or beliefs.

The liberal use of the term sparked many a debate as various characters were labelled as Mary Sues whether accurately so or not. Heated debates have occurred since the definition has gotten muddled over the years. Though, since the term is informal and the definition is quite broad, more than having a clear yes/no decision on if a character can be labelled a Mary Sue, it might be easier to analyze them using a Mary Sue spectrum.

On one side, we have characters who are irrefutably Mary Sues such as the likes of Bella Swan from The Twilight Saga, Anastasia Steele from the Fifty Shades of Grey series, and even the James Bond character. In the middle of the range, we have some characters that may be considered as Mary Sues but are sometimes faced with disagreement over the label. Characters that fall here may be Luke Skywalker from the Star Wars film series and fictional superhero Superman. On the completely opposite side of the spectrum are the characters that spark fierce debate when labelled as Mary Sues. In this corner we have characters like Katara from TV series Avatar: The Last Airbender, superhero Captain Marvel, and Rey who first makes her appearance in the Star Wars universe in Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

The derogatory status of a Mary Sue was created in part by the misogynistic use of the character label to dismiss any strong female lead character whether they are an idealized self-insert or not.

On September 5, Facebook user Sara Lynn Michener proclaimed that “I see we’re going to have to have this conversation again.” Michener illustrated how the nuanced term created by Smith and Ferraro to mean “an idealized self-insertion” has been morphed to mean “women in mainstream published, professional fiction who have implausible hero skills.” Michener goes on to say that men have only begun using this label on women because it threatened the beloved template of male superheroes that exists. “Because their internalized belief that women are inherently lesser is so deep,” she explains that “if women can do it—suddenly they don’t think it’s all that great.”

Even Smith has noticed the problematic trend, with “people who would say anytime there was a female protagonist that’s a Mary Sue.” The term was weaponized against any strong or capable women that appeared in fictional worlds. While the Mary Sue label should be applicable to a character no matter what their gender is, more female characters were being called it than male ones. A double standard surfaced as girls who were just too powerful didn’t sit right for some viewers, leading them to dub the characters as Mary Sues, while male leads with the same amount of power were left “free” of the label. Despite being applicable to any and all characters, women have been looked at with a far more critical eye.

Michener’s post received over 14 thousand reactions and 12 thousand shares. Majority of the comments were in support of Michener’s point.

Some even showed their support by encouraging her to ignore all the hate comments and laugh at them instead.

The term Mary Sue itself does not have an inherently sexist nature. Although it has been weaponized, it was quite literally just a critique on the written complexity of a character, regardless of sex and gender.

Mary Sue provides creators with a word of caution. While it is okay to include self-insert characters, it may be better to make them real. It may be exciting and easy to get carried away imagining yourself as perfect, but at the end of the day, no one really is. The characters we come to know and love the most are real and flawed (and not just in a quirky way that only makes them more loveable). Some stories are made better with self-insert characters, just make sure that they are real and complex—just the way we like ‘em.

For viewers, Mary Sue should push them to go deeper into their character analyses and reflect on why they might label a character as a Mary Sue whether they are deserving of it or not. The minimum requirement of being a Mary Sue is that a character is an idealized self-insert, not that they are female and powerful.

Other POP! stories you might like:

Unpopular opinion: Mankind has a problem with its fixation with true crimes

The future of Philippine live theater, post-pandemic

Ride and dine in Sky Ranch Tagaytay

17 More jeepney signs that also go hard