It should not require a chess genius to spot every excellent detail about “The Queen’s Gambit,” the hit miniseries about an orphan girl who beats the odds to become a chess champion, based on the novel by Walter Tevis. After all, they’re not as far out as a series of moves before one can say “check.” For this viewer and lousy chess player, at least, they are easily manifest, if one would simply take the time to look.

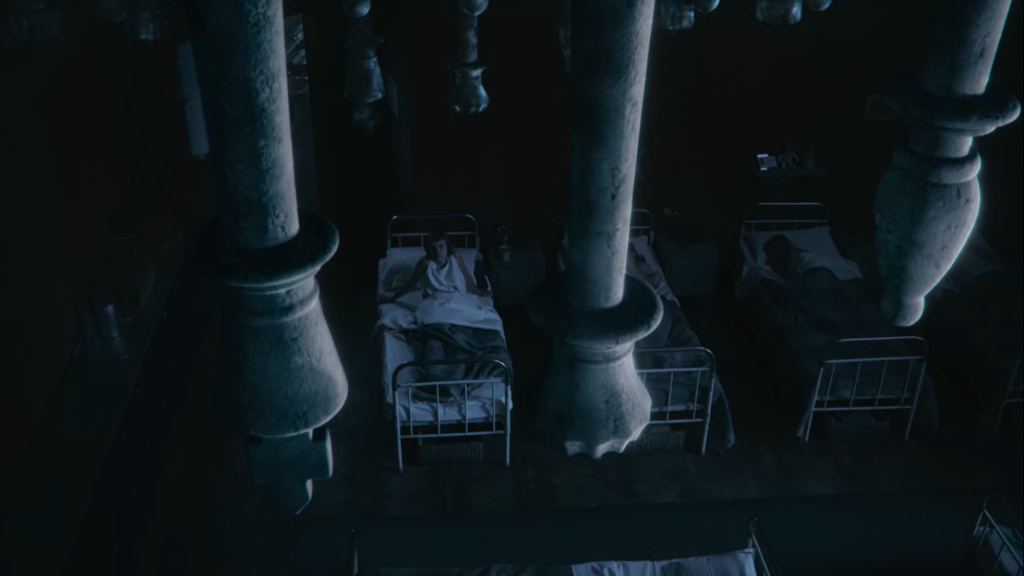

Just take the case of those imagined chess pieces gliding upside down in ceilings, or the block-by-block montage for the Ohio-set national championship – the photography was able to flesh out the wonder and suspense of a highly cerebral game. The stylishness of the 1960s was captured by the design, but so is its interior gloom, the flip side of what’s popularly known as a vibrant era. The orchestral score soars while the music of the times curated was accurate. There’s Beth reaching for her adoptive mother’s hand to the tune of “End of the World” by Herman’s Hermits, after she said goodbye to a man she bore a torch for, and after she turned her back from a humiliating tournament loss. Then there’s Beth again, all grown up and seductive as she dances to the tune of “Fever” by Peggy Lee, before the aching Beltik.

And then there’s the cast who all turned in unforgettable performances – from the basement chess tandem of the 9-year-old Beth and the janitor Mr. Shaibel, played by Isla Johnston and Bill Camp respectively, to the lead Anya Taylor-Joy backed by Jacob Fortune-Lloyd, Harry Melling, Thomas Brodie-Sangster, Moses Ingram and Marielle Heller. Taylor-Joy’s at-times-icy and always-determined Beth is noteworthy for not giving her orphan character the slightest shred of anything I should feel pity for, and rightfully so, because she’s a wonder kid on her awakening towards being a queen.

It’s this dark queenliness and the unique makings of it which I personally find most powerful in “The Queen’s Gambit.” This is evident in three major themes in the story, easily discernible to anyone. I believe these are the very things that Beth learned the hard way, after she finally allowed herself to see and feel, and eventually receive.

Mentor-mentee, mentee-mentor

I’ve earlier mentioned how Taylor-Joy effectively portrayed a grown orphan whom we were not given a reason to pity. The same can be said for Johnston as the younger Beth, who was even fresh from the trauma of losing her biological mother. Beth is naturally hardened, so it’s no surprise that she is not intimidated by the janitor Mr. Shaibel and his turf that is the basement. This janitor, after a glimpse of Beth’s potential to play chess – she recites to him the moves of some pieces which she figures out herself – agrees to teach her.

He teaches her the basics of how to win and when to accept defeat. He introduces her to a chess group leader who exposes her to her first taste of exhibition matches against a number of schoolboys, simultaneously. He punishes her with no matches after she hurls profanity at him. He loans her $10 even after she has left the orphanage, so she can pay registration for her first official tournament. He fulfills the role of the tough yet giving mentor, and this is almost a given in any story with a mentor-mentee element.

But the take of “The Queen’s Gambit” on the mentor-mentee dynamic brought me to an unexpected revelation when Beth, in a singular moment of a tender breakdown, realizes that the janitor who gave to her from his limited means also received from her. By keeping tabs on her achievements through the years, as seen from the clipboard he kept on the wall of his lowly world in the orphanage, he may have somehow tapped into a silent source of sustenance. For one who’s a fan of mentor-mentee narratives, this execution is something I have never seen before, because the lead-up has been unseen, like a checkmate from nowhere.

Sure, there have been numerous such stories and films of mentors fading away in the background, only to be returned to by the mentee who would be moved by a discovery of the by-then dead mentor’s unspoken or perhaps insufficiently articulated love, all the while. For example, let’s remember the collection of kisses by Alfredo for Toto in “Cinema Paradiso,” and the nearest Beth-Shaibel equivalent I can figure may be the laminated letters of Mary posted by Max on the ceiling in “Mary and Max.” But in all these, it is still the mentee who benefits from and is enriched more by the mentor’s love.

Only in “The Queen’s Gambit” do I see a deliberate attempt in the script to show that Beth and Mr. Shaibel are truly of equal footing, because not only are they both outcasts and outsiders, they were also both able to hold each one up through the years, with a set up for this revelation being impeccably paced and prepared. For those of us who may have feared that Beth’s failure to reach out to the janitor, brought about by her obsession to always win, may have caused him to languish, we are ultimately proven wrong. Because yes, Beth benefitted from the foundation that Mr. Shaibel set for her, but Mr. Shaibel apparently reaped from her victories as well. He found in them a quiet glory, and he surely was happy, and so kept up. Just like Beth, he is not someone who needs pity, and more so because he has been dignified by his pride about her, and his joy and love.

Men, men, men

The second most notable aspect of “The Queen’s Gambit” for me is its wise and sensitive exploration of Beth’s relationships with the men who all started out as her competitors but eventually become her romantic interests. Each unfolding actually has an element of surprise – always, I never saw it coming. I did not expect the matter on Townes’s sexuality, nor Beltik’s call in the middle of a rainy night, nor Watts suddenly grabbing Beth by the arm to ask if she still liked his hair after his dismissal days earlier that there is not going to be any sex.

Each of Beth’s relationships with these three men is understated, subtle and devoid of hostility. These relationships are also not made the centerpiece of her story. The men or her decisions about them are never the cause of any of her failings because they are not even her real adversaries, and she only needs to look in the mirror to see who that is.

Even more, I love that these men unite to join her ranks before the big battle, and that ultimately, she acknowledges their role in her life, for better or worse. She also accepts their support when she on her own is already able to support herself. The help they give her is reinforcement, therefore, not rescue. In Beth’s life, the men are allies, never saviors.

The truth about ‘the strong and independent woman’

Any orphan narrative will have in it characters that serve as the orphan’s found family. But “The Queen’s Gambit” is not our typical story about an orphan who triumphs in life with melodramatic flourish. It is a multitude of stories about a woman, all rolled into one – because it is also a coming-of-age, a period (and a hint of social) drama, and technically a sports saga. Beth the woman’s found family in this heady mix therefore does not just stand in as surrogates.

Just as Beth, in her best form and battle-ready state, welcomes the full support of the men, the entirety of her found family’s real purpose, all the way from Mr. Shaibel and Jolene to her adoptive mother Alma, becomes clear: they have always been present throughout her life and her real triumph is in her acceptance that for even someone like her who is strong and independent, it’s OK to ask for and/or accept help.

This was a victory long and hard in coming for Beth because her own mother, her mother by blood, herself failed to acknowledge that she needs help, and does actually only ask for help until too late. When she failed to receive it from the man she asked it from, a man who appears to be Beth’s biological father, she does not even consider to think that there can be support from others. Hampered by an unfortunate genius-madness and destroyed by misplaced pride and anger, this mother has hammered into the young Beth’s mind that “the strongest person is the person who isn’t scared to be alone.” Naturally, Beth grew up believing that she is “fine being alone.” Not until she slipped into a downward spiral is she forced by circumstances to face that being alone does not necessarily equate to independence, and that independence does not necessarily require the shunning of others.

So the queen from within Beth emerges, rich with gifts received from the people she least expected, people not bound to her by blood, but who nonetheless care. And since she has accepted these just in time before facing the strongest Russian, I no longer feared for her coming into that final match. No matter how he opens or how she defends, the champ, the queen, the woman has won. NVG

RELATED STORIES:

‘The Queen’s Gambit’ breaks streaming record for limited series

‘The Queen’s Gambit’: From chess prodigy to fashion influencer

The victorious ones: ‘Gameboys’ wins best web series in Seoul indie fest