Warning: May contain spoilers.

Joseph Israel Laban’s Baconaua (Sea Serpent) tells the story of three siblings trying to make it on their own in a small island in Marinduque. Ninety days after their father goes missing at sea, the eldest child Divina (Elora Españo) has no choice but to have him officially declared dead. Between worrying about how she will raise her siblings Dian (Therese Malvar) and Dino (Juan Miguel Salvado), both of whom seems to rebel against her authority as the new head of their family, and mourning for the passing of their father, Divina’s life is made even more complicated by events that occur after they find the shores of their small town filled with thousands and thousands of apples.

Laban makes use of mythology and folklore in exploring the underlying issues that trouble the small community, a technique he has used in his previous films. The title of this movie pertains to a mythical sea serpent that the villagers believe to be lurking in the waters that surround the island. Folklore would have them believe that it is the Baconaua who causes locals to disappear at sea, their bodies never to be found again.

The use of folklore to explain dark and difficult realities is a well-documented phenomenon in a lot of cultures. Sociologists and anthropologists believe that part of the reason why fantastical creatures like sea serpents and aswangs exist in our belief systems is the need to find an alternate albeit mythical explanation to terrible and very real events in the world.

In his study entitled “Sa Pusod ng Lungsod: Mga Alamat, Mga Kababalaghan Bilang Mitolohiyang Urban” wherein he researched the development of urban folklore in the Philippines, writer and professor Eugene Evasco wrote:

“Interview results from various urbanized locales… corroborate what sociologists and anthropologists have previously concluded, that the tensions due to urbanization, alienation, politics, technology, militarization, ecological degradation, and industrialization have been instrumental in the creation of modern folklore.”

In the film, the myth of the sea serpent is how the villagers make sense of the disappearances of their loved ones. It is much easier to tell children that a monster is responsible for the multiple deaths in their town rather than explain the fact that the sea is cruel and deadly as much as it is a generous, benevolent source for both their nourishment and livelihood; that it gives and takes life in equal measure. The Baconaua serves as a metaphor for the dangers of being at sea which, as fisher folk, they have to live with every day.

The film can also be viewed as an exploration of our colonial past, with the Baconaua representing the dangers that came to us by sea. As an archipelago separated from any other landmass, all those who invaded and colonized our nation came by ships. This post-colonial motif is reinforced and, quite frankly, given away by Laban’s decision to include the Spanish and English versions of our national anthem in the movie.

We find the community officials hunting down the “taga-labas” (outsider), as they constantly referred to him in the film, that arrived on their island along with the apples that washed on their shore. In our history, outsiders have brought sinister things along with the seemingly good– colonization brought us closer to the technology of the western world but it also erased our identity and enslaved our people. And in the film, the bounty of apples is not just the good fortune it appeared to be.

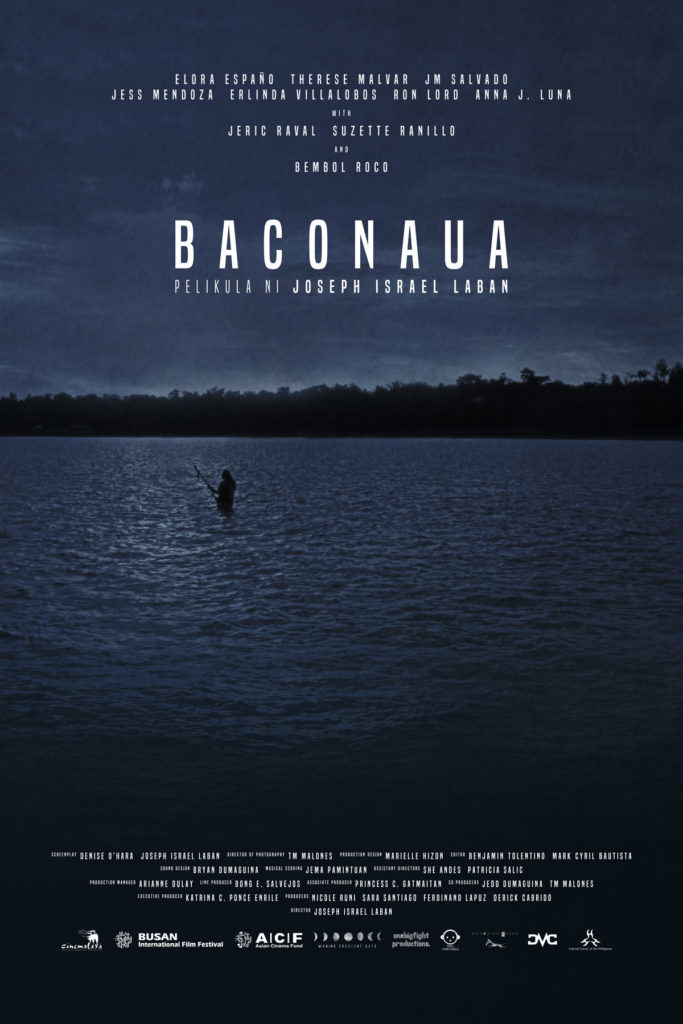

Baconaua is a visually stunning film, winning a well-deserved Best Cinematography Award for its portrayal of island life. Some viewers commented that the film was literally so dark that they could hardly see what was going on, but it turned out to be projection issues in some cinemas.

Given the gravity of its themes, Baconaua faced a big challenge in presenting it in a way that would resonate with viewers. The film requires much thought from its audience, with its intended meaning not being immediately clear after a single viewing. The pace of the narrative is slow, making it difficult for those that do not have the patience for this kind of story-telling. You constantly get the feeling that something big is about to happen in the next scene while watching, and this foreshadowing felt a tad too drawn-out.

Baconaua is one of those films that would suddenly make sense to you long after you’ve seen it, maybe even when you’re not consciously thinking about it anymore. It is one of those films that you can appreciate better once you’ve had the time to ruminate about it. It may be a bit cerebral and inscrutable at times, but it is an insightful exploration of our nationality and history.

—

Baconaua was the winner of the Special Jury Prize award at this year’s Cinemalaya Festival. Joseph Israel Laban won the Best Director award in the full-length feature category, and Director of Photography TM Malones received the Best Cinematography award alongside Ike Avellana of the film Respeto.

Baconaua was screened at Ayala Malls Cinemas (Glorietta 4, Greenbelt 1, TriNoma, Fairview Terraces, U.P. Town Center, Solenad, and Ayala Center Cebu) as part of the 13th Cinemalaya Film Festival held last August 5-13, 2017.